|

| Dr. Jacobus |

When she informed her high school guidance counselor that she “wanted to be a dentist” she was quickly advised that she could, as a girl, be a dental hygienist instead. She did not want to settle for that. But Paula lived in Kane, Pennsylvania, with a population of five thousand and there were no advanced placement, or AP, classes; she had to “fight” to take physics, humanities, and higher math to get into a good college.

Paula is now Dr. Paula A. Jacobus, a fellowship-trained geriatrics specialist.

Her college-educated mother (1930-2013) taught high-school English, and her father (1927-2000) was “a good car salesman” and businessman whose own college studies were cut short when he was drafted during World War II. They were both concerned when Paula, their firstborn, was two and still not talking. They were afraid that she was slow. Afraid that she would be below average.

They realized that the Catholic school classes were much too large for a single nun to provide individualized teaching, so Paula (and her siblings) went to the public school a block from home. It turns out that Paula was not slow, of course, just careful. And of the 160 students who graduated high school with her, Paula was one of only ten who went on to further education.

|

| Postcard rendition of the Kane business section at some time between 1930 and 1945 (from Wikimedia Commons) |

(Paula wasn't the only one in the family drawn to a career in medicine. Her sister Susan is an oncology nurse in Ventnor, N.J. and her sister Judith practiced medicine for 20 years before deciding to become a Catholic nun; she lives in, get this, St. Malo, France. Judith is her "Sister sister.")

Before we get to her unusual college experience, let’s see how the future geriatrics expert was drawn to the elderly. As a child, she spent a lot of time with her Italian grandmother. “Nonna was a wonderful cook,” said Paula, but she could not read (any language). So when she lovingly “read” a picture book to the kids she made up a story. And she left out the violent parts; the cat, for example, did not catch and eat the mouse.

And Paula’s first job as a teenager, at 15, was to stay with an elderly woman who simply needed someone to help her get up at night. At 16, she served as the chauffeur for her 96-year-old neighbor, two doors away, who had purchased her cars from Paula’s father’s auto business. She had her own room in the woman’s home, a definite luxury for a girl with four younger siblings. Paula said, simply, that she “always liked older people.”

Okay, back to her formal education.

College

When it was time to apply for college, small-town Paula didn’t actually have a lofty or special place in mind. And, as we have seen, the unhelpful school counselor didn’t provide meaningful guidance.

So, how did she get to the very highly-regarded St. John’s College in Annapolis? “Purely by chance,” she said. She was in a humanities class and doing a report on education. Her father had a business trip to the area, and as she looked into the school’s curriculum she thought that it sounded “pretty weird.” So she went on the trip with him.

|

| The "Old Library" at St. John's (from Wikimedia Commons) |

She was intrigued by their educational approach. “It was the most amazing thing,” said Paula, because (unlike in her high school) “everybody was there to learn.” And (this is surely unique) each student took exactly the same courses! As the daughter of an English teacher, she couldn’t resist.

You “start with Homer,” she said, “and over the four years, you read the classics,” the primary sources, in literature, philosophy, history, and the sciences. And discussed them, and picked them apart in small seminar settings. You also took two years of Greek and two years of French and some math. While at St. John’s you were forced to develop the skill and the habit of critical thinking, of thinking for yourself, she said.

According to their website: “St. John’s students learn to speak articulately, read attentively, reason effectively, and think creatively.” They "practice radical inquiry" and are urged to "establish habits of civic responsibility."

The noted humanist physician-turned-ethicist and teacher Dr. Leon Kass was one of Paula's important tutors. He was a “really really good seminar leader” and he took her (as a freshman) to the Kennedy Institute of Bioethics to “hang out.” Paula said, reflecting, that this “might have been a pretty significant influence” on why she ended up in medicine. She has read “most of his books.” She enjoyed the intense experience at St. John’s and graduated in 1978.

|

| The 1978 graduating class at St. John's, Annapolis (from their website) (If you can't immediately spot Paula, she's seated in the second row on the right.) |

Transition to Medicine

After this broad liberal education, Paula knew that she still wanted a career in one of the medical fields. The only two doctor role models in Kane were husband and wife, Charles and Elizabeth Cleland. Elizabeth (affectionately known to the Jacobus family as “Dr. Betty”) had to give up her pediatrics residency when she got married (not pregnant, mind you, just married). Nevertheless, she was the one who took care of the kids in the small town as her husband tended to “the sicker adults.” Though Paula couldn’t (she was told) be a dentist, she could (it was clear to her) become a doctor.

So she went to Bryn Mawr College for a year to take the required premed science courses she couldn’t get at St. John's. And in 1980, after a year off, she began her studies at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School (the country's first medical school).

Things were pretty difficult at first, she said, as they crammed all of the basic science stuff into the first ten months and Paula had arrived with only “the bare minimum” preparation. However, in her clinical years, she quickly caught up with her more single-minded classmates.

|

| Penn's medical campus 1829-1871 at 9th and Market in Philadelphia (from archives.upenn.edu) |

While she was In medical school planning her future, she thought about doing something familiar, family medicine. But that new “specialty” was frowned upon at Penn. So she dropped that and considered going into either internal medicine or pediatrics. During her three-month Peds rotation at the York Hospital (affiliated with Penn, then), “three or four kids died.” She was shaken by that and concluded that pediatrics was “not the way to go.”

Following Medical School

After medical school, Dr. Jacobus chose to come back to York for a three-year residency in internal medicine. She followed this with a fourth postgraduate year of her own design where she was especially influenced by (the also well-read) Dr. J. Wolfe Blotzer, the program director. Her make-shift “office” was adjacent to his, and they often sat and talked about what was on their minds.

She had learned a lot during a three-month rheumatology rotation with Wolfe and even considered going into that specialty for a while before choosing to focus on the care of older individuals. (She lamented the fact that the intimate mentor-mentee relationship she was privileged to enjoy as a resident is no longer the way things are done.)

While at Penn, she was taught by Dr. Laurence Beck, a nephrologist who went on to do and teach geriatrics, so, when the time came, she wanted to go back to Philadelphia to train with him. She did that, but when she soon heard that “Larry was leaving” she applied to the highly-regarded UCLA fellowship for the following year. But it turned out that they had an unexpected opening and she was accepted for that current year.

|

| Dr. Reuben |

Return to York

Dr. Jacobus returned to York with the idea of joining another physician in a new geriatrics program, but by then he had already changed his mind and gone into administration. So the staff waited anxiously for Paula for six months. Upon arrival, she had to go it alone and it was difficult. There were vexing personnel issues and she went through six different administrators in five years.

Marta Smith, MPH, (with whom she is still close) was the sixth; they got along and “moved things forward,” but “not to where they should have been.” Dr. Jcobus realizes now that she “didn’t have the skill set to run a geriatrics assessment program” and that “it wasn’t meant to be.”

So, as she was “pretty burned out” after six or seven trying years, she decided to stop doing just geriatrics. She had nothing specific in mind when she decided to talk to nephrologist-turned-general internist Cyrus Beekey for his advice. Cy, it turns out, was looking for a partner. Paula stepped in and worked with him in private practice “for quite a few years.”

But, after a while, it became clear that “private practice (of internal medicine) was dying” (was being slowly choked off). Dr. Beeky saw this and joined the expanding WellSpan Health system. Paula resisted and stayed independent as she continued to do general internal medicine along with some geriatric work in nursing homes. She was happy.

But she had “health problems” along the way, including breast cancer at 43 and the development of diabetes requiring insulin. She didn’t let these setbacks slow her down and she only missed a single scheduled on-call stint. But years into her busy practice she began to worry about how her patients would fare if “something happened” to her and she wasn’t able to continue to take care of them. So Dr. Jacobus thoughtfully arranged for another well-trained physician, Dr. Heui Yoo, to take over her practice as she planned her “semiretirement.”

Retirement on Hold

In fact, she might have retired altogether (“Life is short; do what you want to do,” noted Paula.) were it not for (another) unexpected turn. Within days of setting things up to allow herself to wind down, Dr. Jacobus got a “cold call” from the large Lehigh Valley Health Network in Allentown about 90 miles from York. They were looking for another geriatrics specialist.

It turns out that she had interviewed with them in 1996 when they were searching for someone to head their geriatrics program. At that time, she would have taken over for a blind doctor “who was a wonderful physician,” she said. But another administrative job was not for her. (The sightless doctor was Dr. Francis Salerno, the same doctor who “saw,” as they trained together in Reading in the 1970s, that my husband would become a neurologist.)

This new offer from Lehigh was appealing and suited to her skills and she applied. It took a while “to get on board,” but she eventually started there in March 2015. “It’s been a great place to work,” she said. She initially did half-days at the small Luther Crest Nursing Facility and half-days at the comprehensive Fleming Memory Center for individuals with (or concerned about) dementia.

|

| Lehigh Valley Hospital (from LVHN) |

As a Patient

She is not pleased, however, as she has seen the breakdown of the primary care model of coordination of medical services she experienced during her formative training years. She receives her own care through her employer’s system, and she said that she’s already had three different primary care internists in less than seven years.

Her endocrinologist, for her well-controlled diabetes, has been stable and reliable, sure. But when she needed a dermatologist for terribly itchy (undiagnosed) psoriasis she “couldn’t get past the front desk.” And even as a physician within the system itself, she was stymied when she needed to see a specialist or even when trying to see her regular internist for a week of gnawing belly pain that was due to a ruptured appendix.

And exactly a year ago, on her sixty-fifth birthday, 21 years after her initial shocking diagnosis of breast cancer, she woke up, rolled over in bed, and felt a hard lump in her breast. She knew that she had to have a diagnostic mammogram, but setting this up was needlessly difficult and she was “scared to death” for nearly three weeks until she got a study and it was determined that the lump was just scar tissue.

These frustrating experiences were quite unlike what transpired when she was diagnosed with breast cancer more than twenty years ago. She had called Dr. Eamonn Boyle’s oncology office to make an appointment “for a new patient.” When they asked who the patient was and Paula told them it was she, herself, they said, “Five o’clock.” (As Dr. Jacobus recalled this story about her cancer, and that doctors used to take care of each other, her voice cracked and she cried softly.)

Alzheimer’s Disease

Seeing that obtaining timely health care has become a problem even for physicians, I wondered whether improved treatment of Alzheimer’s dementia, the disorder she mostly sees now, makes up for that lack. Unfortunately, it doesn’t. Dr. Jacobus said that donepezil (Aricept) and the two other similar medicines for Alzheimer’s “might (at best) slow the progression by six months for 10-20% of the patients.” She will prescribe them if requested, but she doesn’t “push” them, since she doesn’t see any “appreciable degree” of improvement. The same can be said for another medication for Alzheimer’s, memantine (Namenda).

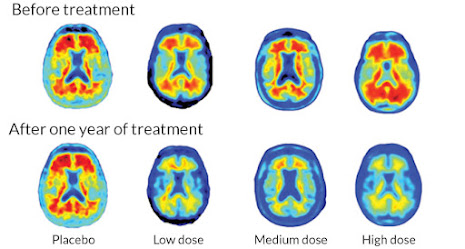

When Biogen’s anti-beta amyloid monoclonal antibody Aduhelm, designed to remove clumped deposits of the amyloid protein that are one of the hallmarks of the disorder (tau "tangles" being the other), was given approval earlier this year over the objections of the independent reviewers the phones at the memory center were “ringing off the hook.”

But the enthusiasm for this treatment to slow or stop the dreaded disease process itself, not just treat the symptoms, faded quickly. As a result of the weak and inconclusive clinical data despite the evidence that amyloid was removed, and the seriously suspect accelerated approval process, this very costly medication with potentially serious side effects is currently available only in the setting of a controlled study.

Enrolling patients has been painfully slow and might end altogether as the industry funding dries up and other promising treatments are pursued instead. And, importantly, not all researchers believe that trying to remove the amyloid plaques is the right approach, as the phosphorylated tau tangles disrupting nutrient transport within cells may be more critical.

|

| PET scans showed that deposits of amyloid (in red) were removed (from www.sciencenews.org) |

PET Scans and the Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s

What about making a diagnosis, one of the important tasks of the geriatric specialists at her center? Until relatively recently, Alzheimer’s was a so-called purely clinical diagnosis, made after other causes of dementia have been excluded. There was no definitive imaging or blood or spinal fluid test for the condition, and it was only diagnosable with absolute certainty at autopsy.

Being able to see the accumulating amyloid beta deposits during life with special PET scans has aided research studies (as those for Aduhelm, noted above). But using any type of PET scan (there are several, each showing different things, but all are very expensive) for individual patients with dementia (or a suspected dementing process) isn’t precise, and may be misleading. Positive scans make the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s more likely and negative scans while reassuring, don't rule it (or other causes of dementia) out. Misdiagnosis is still not uncommon.

So Dr. Jacobus is currently “starting a quality improvement project about PET scans” at her facility. She said that of the five practitioners in the office, two don’t order them for patients: she and Heidi Singer, CRNP, (who was trained by Dr. Salerno). The other three do. Patients and practitioners, she noted, both need to be aware of the limitations of imaging.

But (and here’s an important point) “even if we can prove today that (our patients) have Alzheimer’s, we’re not going to do anything to majorly impact that,” Paula said. (As a resident at the York Hospital many years ago, in another lifetime, she was taught that “you don’t order a test if you are not going to do something about the results.”)

For an accurate diagnosis, it may be preferable, she noted, to carefully examine patients over time to see if their memory deficits or other cognitive or behavioral problems worsen, consistent with dementia, either Alzheimer’s or something else.

But sometimes patients and families want certainty, they want to know for sure what they are up against, and push for (what they hope will be) a definitive test. They feel the need to be their own advocates within the large complex regional health systems, a role that Dr. Jacobus, as a patient herself, understands.

In any case, in the absence of an effective treatment for the very slowly developing brain disorder (it likely starts decades before symptoms are detected), a major focus at the busy but understaffed center in Allentown is on education (as was repeatedly emphasized during her training years under Dr. Blotzer). And this group effort is carefully tailored to the specific needs of each particular family (As, in Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, “every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”).

More Technical Neurology Stuff (with the neurologist's long-winded input, of course)

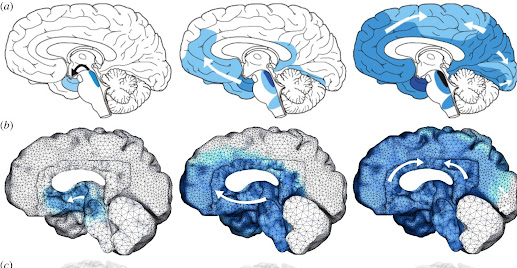

Scientists have not determined exactly what leads to the gradual accumulation of the toxic misfolded amyloid-beta and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins that damage the delicate synaptic connections between neurons and result in the death of the neurons themselves. They do know that the spread from the initial sites in the brain areas for forming memories (the hippocampi) proceeds along the connecting neural pathways.

|

| Mathematical model of the spread of misfolded tau through the so-called connectome (from royalsociatypublishing.org) |

Early-onset disease, seen in much less than 5% of patients, is caused by mutations in amyloid precursor protein and presenilin genes; the much more common late-onset disease is related to a multitude of interrelated factors, both genetic and environmental (as for most chronic disorders).

Research has shown that lipid metabolism plays a very important role in Alzheimer’s. Apolipoprotein E (apoE), through interactions with cell membranes, regulates the clearance of damaging extruded amyloid beta fibrils before they clump up. Carriers of one of the three forms of this protein, apoE4, have the early accumulation of amyloid beta deposits, substantially increasing the risk of developing Alzheimer's down the road. Carriers of apoE2 have a lower risk while the apoE3 is neutral.

The gene variant coding for apoE4 is found in about half of those with Alzheimer's; people with two copies have about a 60% likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s by age 85 compared to 10-15% of those without the gene variant. And so, there are other important factors in play.

|

| Prevalence of Alzheimer's by age (in 2005) (from ResearchGate) |

It turns out that age itself, living a long life, poses the greatest risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s (as it does, for example, for hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, osteoarthritis, Parkinson's, type 2 diabetes, and cataracts). Up to 50% of those older than 85 may be affected by Alzheimer's dementia. The next most significant risk is having a parent with the disorder, especially a mother (who supplies us with our mitochondrial DNA). But the genetics is way more complicated since more than 800 genes may modify the metabolism of the amyloid precursor protein.

The misfolded tau protein story is only beginning to be understood.

We are stuck with our genes (so far) but genes are turned on and off (through epigenetics) and there are modifiable risk factors for the feared condition. There is a significantly heightened likelihood of Alzheimer’s dementia in people with vascular disease, hypertension, and (especially) insulin resistance and overt diabetes. Mid-life central obesity, repeated head injuries, heavy alcohol use, cigarette smoking, lower educational level, social isolation, untreated depression, inactivity, poor diet, and hearing loss all increase the chance of developing dementia.

In fact, it is felt that anything that influences the health of an individual through life and the rate of aging is a potential factor.

Buffers against developing substantial late-life cognitive impairment include adequate treatment of hypertension and dyslipidemia, a habit of regular exercise (the link is surprisingly strong), lifelong cognitive pursuits (learning something new; doing something new), getting enough sleep (allowing removal of toxic debris), mindfulness meditation (shown to lengthen the protective telomeres at the tips of our chromosomes ), and regular social engagement (our brains are shaped by other brains).

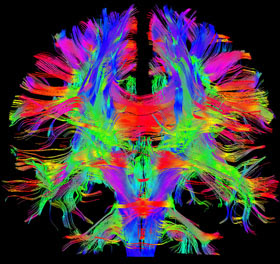

And if you have more interconnections and more synapses to begin with you can lose a good bit and still function well. And, contrary to formerly accepted dogma, we have stem cells in the brain (and especially in the hippocampus) that can generate new neurons and supporting cells when stimulated to do so.

|

| Image of brain interconnections (from the Human Connectome Project) |

We can improve the chance of our brain aging well if we make the right choices early enough in life.

The Future?

I asked about her thoughts on the future of medicine. Paula is particularly worried about the quality of care in rural areas. For example, her nephew in Kane was (accidentally?) shot recently by his girlfriend. He is now a T4 paraplegic and when he had “horrible” diarrhea the other week the diagnosis of C. diff (that was obvious to Dr. Jacobus when she heard the story) was missed in the ER as he was initially told he had prostatitis. And years ago, when her mother had a brain tumor, a benign meningioma, she had to make three trips to the local ER before her symptoms were taken seriously enough to result in a brain scan.

What about telemedicine (for these remote underserved areas)?” I asked. “I don’t think that’s the way to go (for most things),” said Paula.

Looking at the other side of the medical encounter, another one of her nephews has just started an emergency medicine residency in Cincinnati. She is uneasy as she sees the shortened rotations and the lack of hands-on learning at her current institution. And she is uneasy as newer trainees seem to rely less on their clinical skills while they rush from patient to patient and “do a lot more tests.” This (over-) testing greatly increases the societal cost of healthcare, likely to the point soon, Paula believes, where it will simply be no longer affordable.

As it is, we spend a lot more on healthcare per person than any other wealthy country. And the future burden to society to care for the rising number of people with Alzheimer's as our population ages is expected to be enormous.

She feels that doctors need to be mindful of this and aware that spending more time with patients can result in less need for costly studies and more efficient medicine. (I found online that Dr. Jacobus has a master’s degree in public health, an MPH, from Loma Linda University in California; she failed to mention that credential during our interview.)

Paula feels fortunate that she can still take as much time as she needs in the office since many of her elderly patients are confused and lots of things have to be sorted out. For example, their long medication lists (one of her patients brought in 67 bottles, she said) need to be simplified. In fact, Dr. Jacobus tries to limit her patients to five essential medicines. And when they come back for a follow-up, having stopped potentially harmful unnecessary pills, ”they are (often) better.” This “deprescribing” is an important new tool for geriatricians.

And as for general advice, she strongly encourages her patients, of course, to remain mentally and socially active and to exercise whenever possible.

Outside Interests

What does Paula like to do when she not doing medicine? She enjoys quilting and belongs to several guilds devoted to that craft. She just finished a classic “attic windows signature quilt” to present to her boss (who is retiring). She made 32 “bright and colorful” quilts for Jessica and Friends, a local faith-based program for adults with autism and other intellectual disabilities. And she has made quilts for Camp Erin for bereaved children. (Her first purchase with her “own money” was, in fact, a sewing machine!)

She loves to travel and the experience of being in a different culture. She has been on every continent except Antarctica, sometimes with a group from Penn State York, and sometimes with her friend Marta. Paula has been to the 400-year-old Oberammergau Passion Play in Germany four times (it is performed once every ten years according to a promise made in 1633 when the town was spared the ravages of the Plague). She doesn’t know where she wants to go next.

|

| Paula and her new Berber friend in the sand dunes of Erg Chebbi, Morocco, on 3/10/20 (the day before the pandemic was officially called) |

So...

When you are a young child with crowded misaligned teeth you need to find a competent orthodontist to straighten things. When you are a somewhat forgetful older adult with missing teeth or no teeth at all you need to find a well-read compassionate geriatrician to help guide the way. Preferably one who’s been a patient herself.

Suggested Readings:

1. "Alzheimer's Disease." from Wikipedia. (accessed 9/2/22) (A very good and complete resource with lots of science.)

2. Cohen, Gene D, M.D., Ph.D. The Mature Mind: The Positive Power of the Aging Brain. Basic Books. New York, 2005. (A reassuring and easy read by the first chief of the Center on Aging at the National Institute of Mental Health, a psychiatrist.)

3. Pachana, Nancy A. Ageing: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kindom, 2016. (A nice overview by a psychologist.)

|

| A braided Challah |

By Anita Cherry 09/10/22