|

| Nikhilesh Agarwal |

There was no more to be said. But the next day the FBI agents returned, asking questions. Once again, he quietly told his fiancée that they were not looking for him. The third time the feds appeared at the door they admitted that they had the wrong man; they were after a different Dr. Agarwal.

Dr. Nikhilesh Agarwal surmised that the FBI did a full background check on him when he applied for U.S. citizenship. There was, thus, no more for him to say. Though he is a “private person” he is “not secretive,” and he had nothing to hide from them, or anyone else. You see, he has no interest in, or talent for, deception.

Dr. Nikhilesh, or Nik (as he is affectionately called by his colleagues) was raised in New Delhi. His father, a strict vegetarian and observant follower of Hinduism, had moved to the teeming city from the foothills of the Himalayas for a university degree and to start a family. He worked in the federal government in an import-export licensing division. He went to law school while he was working.

|

| Beautiful quiet foothills of the Himalayas |

|

| A busy, noisy, not-so-beautiful, but vibrant street in New Delhi |

Moving on. “How did you get into medicine?” I asked. He couldn’t really say. But from the time he was about ten, when his father was not in good health, he knew that he wanted to be a doctor. Not just any doctor, but a cardiothoracic surgeon! He took a “straight and narrow” path. He did the required one year of college before the five-and-a-half years of medical school in New Delhi.

He came to the U.S. at 23. He did an internship at the poorly funded D.C. General Hospital, the only "public" hospital serving the District (until it closed in 2001). He notes that “they had the dubious distinction of being sued for not having a CT scanner” (in the late 1970s).

|

| D.C. General after it was closed and was turned into a temporary homeless shelter (from "The Washington Times") |

But as he looked to the future he (correctly, it turns out) sensed that advances in the medical treatment of heart disease would greatly reduce the need for surgery. So he changed direction and took advanced training in trauma at the Shock Trauma Center in Baltimore, the world’s first facility dedicated solely to the treatment of trauma.

As he told me his winding story, I wondered why Dr. Nikhilesh picked such an obviously high-pressure, technically difficult, messy, and emotionally demanding surgical specialty. So I asked him.

|

| A trauma bay at the end of a messy case |

Asperger's? Now I definitely needed to know more.

It seems that Nik “always” felt that he was somehow different than his brothers; that he was socially awkward; that he was just not interested in what people were up to; that he could easily walk away from things that he liked; that he doesn’t “suffer” feelings of guilt; that he may ignore the people that love him; that he doesn’t return phone calls from family when he knows he should, etc.

However, despite his constant searching for self-knowledge, he “didn’t connect the dots,” until three or four years ago. “The lightbulb went off,” he noted, when he turned on the TV one day and accidentally caught an episode of “The Big Bang Theory.” As he carefully observed the main character, Sheldon, he said to himself, “This is me!”

He immediately went online and answered one of the many Asperger’s screening questionnaires. Well, as it turned out, he didn’t have enough of the required behaviors to make a diagnosis. But he was (and still is) convinced that he lies somewhere “on the spectrum.”

|

| Lorna Wing, F.R.C.P. |

(Medical writer Steven Silberman noted that it was the psychiatrist [and mother of an autistic child] Dr. Lorna Wing [1928-2014] who first used the term Asperger's syndrome [in 1981] for "high-functioning" individuals with the autism traits. Traits that she concisely identified as being difficulties with social interaction, social imagination, and communication. This was not a standard diagnosis until 1992 and it was removed from the DSM V as a separate condition in 2013.

Wing also coined the term “autism spectrum” which “provoked pleasing images of rainbows and other phenomena that attest to the infinitely various creativity of nature." She said that “all the features that characterize Asperger’s syndrome can be found in varying degrees in the normal population” [Silberman, p. 353].)

Anyway, this sudden and unexpected insight into his brain's social and emotional wiring caused Nik to reflect on some of the decisions he made over the years:

Maybe working every other night and being chronically sleep-deprived was not such a good thing for his family. Maybe leaving his family at a social function to “fend for themselves” while he rushed off to the hospital for a sick patient wasn’t the best idea. Maybe not taking a real vacation every now and then wasn’t helpful. Maybe advising a patient’s anxious family members to go home for a rest when their loved one was still unstable in the ICU came off as unfeeling or uncaring.

Maybe he could have done things better if he just knew more about himself.

But what he did know, and early on, was that he could do surgery. That he could manage the complex, stressful, and sometimes chaotic situations that trauma may present. That he loved what he did. That when he was taking care of patients he was in his element.

|

| R Adams Cowley, M.D. |

While finishing his training in the cauldron of downtown Baltimore with Dr. R Adams Cowley (1917-1991), the well-known trauma pioneer, he received inquiring phone calls from York. Neurosurgeon Dr. Ronald Paul and general surgeon Dr. Thomas Bauer wanted to recruit him to start a trauma service for the area.

Dr. Nikhilesh drove north on Route 83, settled in York and carefully developed and grew the complex multidisciplinary program. However, there were (territorial) politics involved in the process of accreditation, and it wasn’t until 1986 that York Hospital was designated as a regional trauma center. Nik led the team and served as director until 2000 when Dr. Keith Clancy was brought in to take over the administrative duties. Nik graciously moved aside.

The service has been quite busy since its inception (with over 2,000 trauma visits last year). After he was no longer director Dr. Nikhilesh practiced general surgery and enjoyed teaching, and he continued to serve the community as a trauma attending until 2015. His practice has changed since then, as he now does vascular and general surgery as an independent physician. He was cut off from the surgical residents for a while but was recently asked to do some teaching again, and he agreed. He feels most comfortable “at the bedside.”

After the tens of thousands of patients he has treated in his career, I wondered if there were any who touched him especially deeply.

“Yes,” he said. There was one particular woman, he recalled. She was a Jehovah’s Witness in her early 60s. She had multiple traumatic injuries (“she was banged up head to toe”) and had profound blood loss. Her hemoglobin was down to a critical 4 grams (the normal is around 12). She refused blood transfusions on religious grounds, and yet she managed to survive more than five months of fluctuating critical illness in the ICU. But the day after she was finally stable and ready for rehabilitation she suddenly arrested.

Dr. Nikhilesh was at an early morning surgical conference when he was informed of the shocking event. He instantly “knew” that she had a massive pulmonary embolism. (He had thought about placing a vena cava filter to prevent this well-known late catastrophe after trauma, but he was worried about causing bleeding.) He immediately left the conference to rush to the patient’s room. He did an emergency bedside thoracotomy; he opened her chest to resuscitate her and remove the clot.

But she could not be saved. He mourned her loss for nearly a week. This was the only individual he truly grieved for other than his father (who died while Nik was in medical school).

(Pulmonary embolism may cause 10% of late deaths after trauma despite measures to prevent it.)

The most common causes of early death after trauma are devastating brain injuries (about 50%), where the neurosurgeon is urgently needed, and severe blood loss with vascular collapse, shock, and multiple organ failure (about 35%), where the general trauma surgeon must quickly survey the situation to identify sources of bleeding to control them as soon as possible. Dr. Cowley, building on his military experience, developed the concept of the first “golden hour” after trauma, during which aggressive care is most effective. Time is critical, and many lives are saved by rapid and coordinated high-level trauma care. (The survival rate at Shock Trauma, for example, is close to 97%.)

How common is the problem? Very. Trauma is the leading cause of death in the U.S. in those under 45, and the third-leading cause of death in those 45-64. It is an extremely serious (and apparently underfunded) health problem.

|

| CDC: Causes of death by age group (unintended trauma is in blue; suicide is in green) |

(Princess Diana, I recently read, was awake and responsive after the tunnel crash. But she was treated on the scene for an hour before being taken to a hospital. She died as a result of critical blood loss due to a “small tear” of a pulmonary vein that “should not have been fatal,” according to an autopsy. On the other hand, when President Reagan was shot he was immediately rushed to a trauma center where he was stabilized within 30 minutes despite massive bleeding due to his chest wound.)

While researching the advancements in trauma surgery I watched an interesting TED talk by Australian Dr. Russel Gruen entitled “Playing God; A trauma surgeon’s view on death vs. science.” He first sought God's help when he was an intern; he returned from work one day to find policemen at his door. His brother had been in a hang-gliding accident. He died. He was 21, and now he was gone. Dr. Gruen found that God could not help.

During his ten years as a trauma surgeon he has looked for divine intervention from time to time, but, sadly, he hasn't seen it yet. However, he sometimes experiences technology coming to the rescue. But when it does not, as is still too common, and the patient gradually succumbs to their injuries, “life, on the way to death, looks like dusk.” The busy trauma surgeon witnesses much sadness.

The progress in acute trauma care in recent years includes the quick transfer to a level 1 trauma center (as the York Hospital has been designated since October 2009), bypassing closer but less well-equipped facilities, rapid resuscitation with blood products (not just fluids, as had been the practice), better control of bleeding (including use of topical agents such as QuickClot, that promote rapid clotting at the site), timely CT scanning, early definitive surgery, and concerted efforts to prevent contamination (since sepsis is a major cause of late deaths), among others (that are way too technical to mention or for me to understand). (Yes, that was a complex sentence about complex tasks that need to be done at nearly the same time.)

Getting back to our subject, Dr. Nikhilesh confided in me that he is a “surgery addict.” What does that mean? For example, after one grueling 40-hour trip to India by himself, when he finally arrived it was two in the morning local time, but four in the afternoon body time. He told his brother (a physician) that he was “so tired that the only thing he was good for was some surgery.” (I think he was exaggerating for dramatic effect, but I’m not sure…)

[How to cope better on long cramped flights? Maybe chair yoga could help.]

|

| Seated forward fold pose (Paschimottanasana) from JURU: "8 Airplane Yoga poses for a long flight." (I still can't breathe!) |

What is on Nik’s mind other than cutting people open and patching them up and sending them on their way? Well, he worries about us. “The human experience is cursed (in its seeming unchangeability),” he said. And “we never really know ourselves. And other people see us and (try to) interpret what is going on in our brains (but) they will never know.”

So he is frustrated as he learns that what we know about others, even our loved ones, is often “completely wrong.” For instance, when his wife sees him and says, “Why are you angry?” and he isn’t angry at all, he wonders (how often this misinterpretation happens). “Others don’t see us with the microscope we think they have,” he said.

Because Dr. Nikhilesh feels that he has the Asperger traits of social awkwardness and a relative lack of empathy he has worked diligently to improve his listening skills and to be more aware of, and sensitive to, the feelings of others.

He reads a lot and thinks deeply. He is concerned, for example, that our children are “taught the 3Rs” but remain unschooled in the “advances in psychology (including the psychology of well-being) over the past one hundred years.” Advances that help us understand ourselves and our role in the essential interconnectedness of the world.

Eastern philosophy informs Dr. Nikilesh that conditions beyond him are (mostly) in control (of what happens next), that there is always cause and effect.

According to a 2018 Medscape article:

Individuals with Asperger syndrome have normal, or even superior, intelligence while demonstrating social insensitivity or even apparent indifference toward loved ones. Indeed, individuals with Asperger syndrome have accomplished cutting-edge research in computer science, mathematics, and physics, as well as outstanding creative work in art, film, and music. Many prominent individuals (e.g., Albert Einstein) have demonstrated traits suggesting Asperger syndrome...An unknown number of adults with Asperger syndrome may be undiagnosed for their entire lives.As Nik strives to learn more about himself, about who he is at the deepest level, about his inner self, his patients and colleagues may be comforted in knowing that they are with the precisely right Dr. Nikhilesh Agarwal; that there is no mistaken identity.

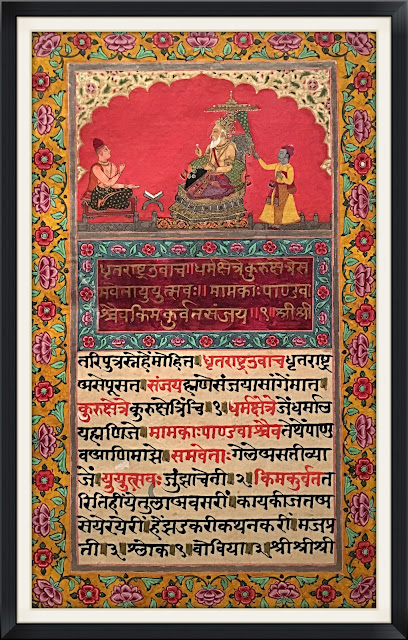

The Bhagavad Gita, the sacred central text of Hinduism, states:

“The wise work for the welfare of the world, without thought for themselves...perform all work carefully, guided by compassion” (3:25-26).

Bibliography:

1. Brasic, James Robert. "Asperger Syndrome." Medscape. February 13, 2018.

2. The Bhagavad Gita: Introduced and Translated by Eknath Easwaran, 2nd edition. Nilgiri Press. Tomales, California, 2007.

3. Silberman, Steve. NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity. Avery (an imprint of Penguin Random House), New York, 2015.

4. Rhee, Dr. Peter. Trauma Red: The Making of a Surgeon in War and in America's Cities. Scribner. New York, 2014.

|

| The first verse of the Gita and commentary in Sanskrit in "Illuminated Manuscript of the Jnaneshvari" Artist: Unknown; Indian; 1763 (photographed by SC at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) |

No comments:

Post a Comment