|

| Steven Pandelidis, M.D. |

“She said,” he went on, “that my father saw her in his busy psychiatric practice thirty years ago, and that he took ‘great care’ of her. She said that she will ‘never forget’ what he told her:

“‘You are not crazy. You don’t need a psychiatrist. You just need to do three things: You need to get a new job, get a new car, and get a new husband.’”

The woman took this unconventional and surprisingly pragmatic advice, and, as things turned out, “He was absolutely right!” she said.

“My dad should have been a surgeon,” said Steve, somewhat cryptically.

(Later on, trying to discern what he meant, my husband reminded me of Atul Gwande’s first book, “Complications.” Dr. Gwande expanded on what has been said, usually disapprovingly, about surgeons: that they are “sometimes wrong; never in doubt.” Atul claimed that “this may (actually) be their strength.” When faced with uncertainty and inexact science the physician wielding the knife must cut anyway; a decision needs to be made and action taken. Words may be thought of as scalpels too; cutting into, cutting away, and shaping the patient’s experience... But back to our story.)

|

| Kirk Pandelidis, M.D. |

Steve’s father (1927-2016) was an immigrant from Greece (after his own persecuted parents left Asia Minor, now Turkey). He settled in York to marry and practice psychiatry. Steve said that his father worked long hours, often seeing patients after dinner until ten at night, and that “he loved what he did.” He “commanded respect” in the community and at the Greek Orthodox church, where he was affectionately referred to as “īātré.”

(Another digression: I didn't understand the Greek word Steve used, and my mind drifted to our family trip to Greece 15 years ago. On the worn Athens streets, I heard people softly calling out “Éla, Éla,” to one another. I wondered what it meant. Maybe it was just a strangely-popular name. On the last day of our stay I asked our taxi driver. He said, quietly, “It means to come closer.”)

Anyway, despite his father’s hectic schedule, the family (he has an older brother and two sisters) always had supper together at six. His dad would sometimes talk about his patients (no names), and the “unbelievable chaos” in their lives.

While there was no push for Steve or his siblings to go into medicine, there was never talk of “doing anything different.” By the time he was in the “ninth or tenth grade” Steve “knew” he would go to medical school.

He graduated from high school in 1979 and during the following summer he served as a psychiatric aide (you read that right, he worked in psychiatry) at the York Hospital. He did this while majoring in French Literature (oui, Litterature franḉaise) at Haverford, and again after his first year of medical school at Penn State Hershey. (Steve dutifully followed his brother Nicholas to both schools, by the way.)

While Steve found these summer interludes “interesting,” he was clearly not going to be a psychiatrist. He was not a fan of chaos. “How did you decide to go into general surgery?“ I asked.

During medical school, he did a fourth-year surgical rotation at York Hospital in plastic surgery. After that, he considered becoming an ENT (ear-nose-throat) specialist. Community practice had little appeal (ear tubes and tonsils and such) compared to a university setting where they did head and neck cancer surgery, but he did want not want to be an academic. At the last moment, he decided to do general surgery. But why? Because he “just liked it.”

Where should he go next for training?

“I thought I might come back to York (after medical school) because I am close with my family,” said Steve. So he applied to his hometown program.

Dr. Jonathan Rhoads, the director of the surgical program at the York Hospital, gladly accepted him for a residency. Steve “absolutely loved” the five years of intense work. He married his wife Julie during his third year of residency. He gradually absorbed the demanding craft of surgery and they kept things simple at home as they lived in an apartment over his father’s office just down the street from the hospital.

(The psychiatric practice was named “Delphic” to honor his father’s Greek heritage. Delphic: pertaining to “ambiguous or enigmatic” advice or predictions.)

|

| Oracle at Delphi (from "The Greek Reporter") |

And strenuous athletic activity is an important part of his routine. Dr. Pandelidis is a serious triathlete who swims, bikes, and runs on different days of the week according to his mood and the weather. He found “Bikram-style” Hot Yoga five years ago and is hooked. He wishes he had discovered it earlier.

The focus of the intense 90-minute classes in 104℉ studios is on three things: “flexibility, balance, and stamina.” They run through the same 26 gradually-more-difficult yoga poses plus two breathing exercises each session. The same sequence over and over. And wherever in the world these classes are given the routine is identical. “You can measure your own progress,” said Dr. Pandelidis. "You compete against yourself and try to improve. It’s pretty nifty.”

|

| "Everybody on your Toes!" (From a hot yoga session at Massachusetts General Hospital) |

Anyway, we can leave the drippingly sweaty and scantily clad athletes in their yoga class and return to Steve's story.

Yes, he liked general surgery well enough, but he also enjoyed the weekly “tumor board” conferences. He listened as the “erudite” oncologists Dr. Miodrag Kukrika and Dr. Eamonn Boyle (each the subject of a previous story in this series) quoted studies about survival curves. He listened as the radiation-therapy specialist, Dr. Greg Fortier, did the same. He listened as one of the laconic cancer surgeons would grunt and confidently announce, “I can take it out!”

As he worked with Dr. Robert Davis (“an important mentor”) and with Dr. Tom Bauer, York’s first dedicated surgical oncologist, he saw an opportunity for his own career. He sought training in the new specialty and he took a two-year fellowship at the University of Illinois in Chicago. "They did a lot of melanomas, head and neck surgery, and a lot of breast cancer, but not many gastrointestinal malignancies,” he said.

When he returned to York Steve joined six other surgeons in an independent group. As he focused on patients with specific cancers his practice evolved, and he views himself now as “an endocrine surgeon.”

I asked him what he enjoys, what he does best. His skill, he said, is doing thyroid and parathyroid surgery, and he does this more than 200 times a year. He told me that there is generally a predictable pattern to the procedures, and said that “if you do the same thing over and over you get better at it.” (He confided later that he also relishes the test of an especially difficult surgical case every now and then.)

When Steve started his career thyroid tumors were much less common than they are now. They were usually found during a physical exam; the gland was palpated, a nodule was felt, and an ultrasound was ordered. But most nodules he sees now happen to be discovered incidentally. They are found when looking for something else. Thyroid abnormalities may be seen, for example, on a CT scan of the chest done after a suspicious finding on a routine chest x-ray, or maybe after an ultrasound of the carotid when working up a stroke, or on an MRI of the cervical spine done for neck pain.

|

| Thyroid nodule (arrow) found incidentally on a spine MRI |

Dr. Pandelidis said that, as a result of the above, “there are too many ultrasounds, too many biopsies, too many surgeries, and too much (use of) radioactive iodine.” The American College of Endocrinology and other similar bodies have developed guidelines to address this excess, but it will take time to change doctors' habits and patients' expectations.

I wondered if someone who’s been told now that they have a small thyroid nodule can cope with uncertainty so that they can leave it untouched while watching for the enlargement that suggests cancer.

|

| The thyroid and the important surrounding structures |

(Dr. Pandelidis reminded me that a similar dilemma is being seen as tiny breast cancers that might never cause harm are picked up on routine mammograms, sometimes leading to fear-driven mastectomy instead of the breast-conserving removal of just the tumor.)

Through diligent practice, constant self-assessment, and immediate feedback, and by doing the same surgery again and again, Dr. Pandelidis has steadily refined his technique. He said that he can do a thyroidectomy as an outpatient in thirty minutes leaving only a nearly invisible scar.

When the challenge is high and the skill level is matched, the surgeon, like the dedicated athlete or the performing musician, can be "in the flow." There is total immersion in the task that seems effortless, and there is a loss of sense of time and self.

|

| Flow chart after Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi "Flow" is when the challenge and the skill level are matched |

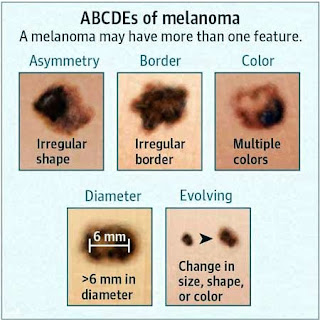

Malignant melanoma is his other major surgical interest and there have been major advances recently in precision diagnosis and non-surgical treatment. This cancer has been increasing in frequency in the last 30 years and is now the fifth most common cancer. There were no new treatments for advanced or surgically inaccessible disease from 1995, when alpha-interferon 2-b was introduced, until a few years ago.

The immune-based targeted therapies approved for melanoma like Opdivo (in 2017) and Keytruda (in 2019) “are amazing,” remarked Steve. These so-called PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors unblock the immune attack on run-away cancerous cells. They are being used to treat diseases that were “not getting a lot of attention” (compared to, for example, breast cancer).

Patients that only a few years ago would have succumbed to their widespread cancer after a few months have now been “walking around for two or three years.” Their “diffuse metastatic disease is all gone,” said Dr. Pandelidis with visible excitement.

His two main interests have something special in common. He said that he “chose (to treat) cancers where surgery makes all the difference in the world.” Where it was once thought that “it was the big surgery that cured breast cancer, now we know that it is the little surgery, along with the help of radiation, chemotherapy, and hormone treatment. But with melanoma, you remove the lesion and lymph nodes that it could have spread to, and most of the time you take care of it.” Early diagnosis is still key. If in doubt about a spot on the skin that looks suspicious, "you should get that checked."

|

| ABCDE Mnemonic to help recognize a melanoma |

As we sat and talked together after his 40-mile morning bike ride with his wife, Dr. Pandelidis was surprisingly relaxed, and I was struck by the sense that he seemed to be an unusually happy doctor; I wanted to know more about that.

I said that we are hearing that physicians have been stressed by changes in the way they are forced to practice in the era of cumbersome electronic health records and increasingly-intrusive insurance companies looking over their shoulders. What was his take?

He said that he “is generally a happy person” by nature (50-80% of general happiness may be genetic according to Haidt), but that he works at being happy too. For example, in his practice he delegates some of the tedious charting work. Simply ordering and arranging for a routine CT scan, a task that used to be straightforward now involves a long list of sequential steps, multiple mouse clicks, and data entry. He hands this off to his capable physician’s assistant. One more job for his support staff; one less headache for Steve.

|

| Documenting exercise, yes exercise, on Epic (from Kaiser Permanente) |

But making sure legal forms are signed, and carefully documenting procedures for the record are his responsibilities alone. This electronic “paperwork” eats into the precious time between surgical cases, the time he needs to ready himself properly for the next anxious patient. He likes to talk to the patient’s family in the recovery room but, due to these constraints, he may (regrettably, he notes) resort to calling them on the phone instead.

But, even though his independent group decided to join the WellSpan system about four years ago and Dr. Pandelidis was reluctant to relinquish some of his highly valued autonomy. He has not let this alter his core values.

He told me that after a surgical cure he still follows most of his patients yearly. They are comforted when he reassures them that their thyroid tumor or their melanoma has not returned. He makes sure that if they have not recently seen, or maybe don't even have a primary care physician they do not neglect other important health issues. He said that this follow-up has become a very rewarding and important part of his practice.

And as he trains and guides surgical residents and students he transmits his way of the experienced physician-surgeon to the next generation.

He teaches them to be flexible, to develop stamina, and to strive to be in balance (though they need not stand on their heads or their tippy-toes).

Suggested Readings:

1. Gawande, Atul. Complications: A Surgeon's Notes on an Imperfect Science. Picador. New York, 2002.

2. Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. The Evolving Self: A Psychology for the Third Millennium. Harper Collins. New York, 1993.

3. Haidt, Jonathan. The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom. Basic Books. New York, 2006